Living donor kidney transplantation is the treatment of choice for patients suffering from advanced renal failure. Frequently (in about 20-25% of the population), donors do not have two identical kidneys—instead there can be asymmetry–differences between the two organs’ size and efficiency in filtration abilities. When a donor has kidney asymmetry, physicians will use the smaller, less efficient kidney for transplantation. When there is more than a 10% size difference between the two kidneys, doctors typically perform an additional test to measure the function of each kidney—known as a split renal function test–as a guide to select which kidney to use for the transplant.

Most transplant centers arbitrarily consider size and functional asymmetry of less than 10% as clinically insignificant (meaning either kidney can be used for transplant), and asymmetry of more than 20% as a cut-off for transplantation, with the concern being that the smaller kidney may not be healthy enough to be desirable for donation.

Dr. Bekir Tanriover, Assistant Professor of Internal Medicine at University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, wanted to examine kidney transplant asymmetry more closely. “There is a very big information gap around this topic,” he says. “When you have more than a 10% difference in kidney size [volume], how does this asymmetry translate into how well the kidney functions once it is transplanted in the recipient? How much kidney asymmetry is actually acceptable? When talking about difference in kidney size, Is ten percent an arbitrary number?”

Getting an Answer with @RISK: How to Assess Potential Donor Kidneys Effectively

To tackle these questions, Dr. Tanriover and his colleagues conducted a retrospective study of 100 kidney donors who had asymmetric kidneys, gathering three measurements from each patient: the kidney size (volume), kidney split function, and semi-quantitative implantation biopsy scores. “We combined these three in an effort to define what the true level of acceptable asymmetry is without danger to the patient, and to determine which of these factors has the greatest impact on recipient outcomes,” says Dr. Tanriover. Their study, titled “Live Donor Renal Anatomic Asymmetry and Posttransplant Renal Function,” will appear in an upcoming issue of the journal Transplantation.

Using @RISK, Dr. Tanriover created a linear regression model and Monte Carlo simulation to predict the outcome of those patients. “@RISK was very helpful, as I only had 100 patients in our data system,” he says. “Using regression coefficients, I could do a simulation as if I had 10,000 kidney donors to visualize how much each variable impacted recipient kidney function after one year.” Using simulation in the model was important, as there are a limited number of living kidney donors, and the low number can make it difficult for a study to differentiate small differences.

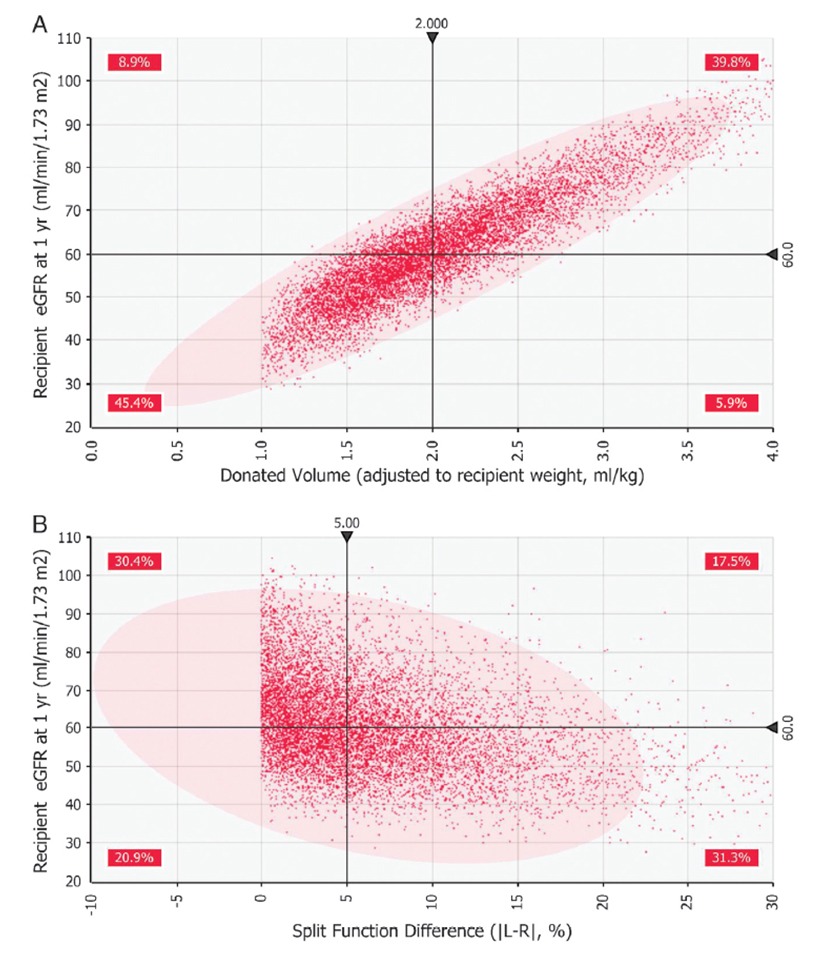

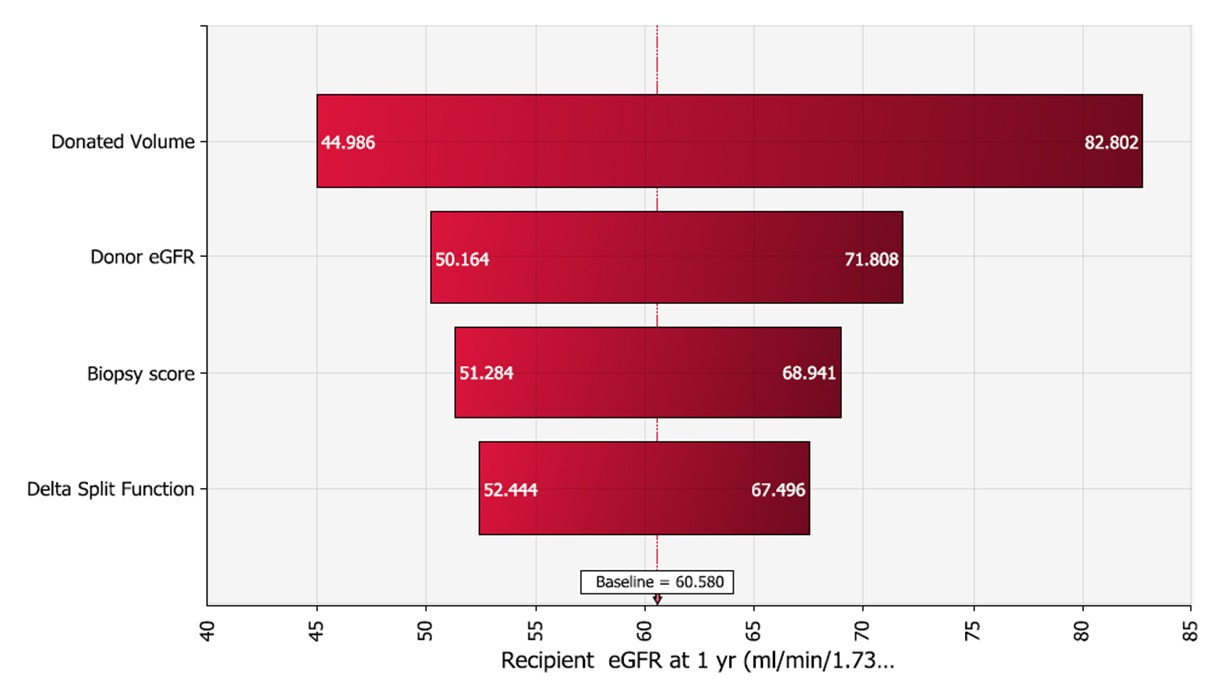

The model showed a clear correlation between donor kidney size (or volume) and recipient outcomes (kidney function at one-year measured as estimated glomerular filtration rate). In fact, the model showed that kidney size was the only variable that truly mattered when it came to the three measurements.

Figure 1: A shows a scatter plot of kidney size (i.e., ‘Donated Volume’) versus the recipient’s outcome (measured as estimated glomerular filtration rate after 1 year). B shows split renal function test results versus patient outcome. Graph A shows a clearly defined positive correlation between kidney size and patient outcome.

“We found that the results from the split renal function test should not necessarily be part of the clinical decision criteria,” says Dr. Tanriover. “In fact, the split function test and the biopsy should be eliminated as part of the kidney evaluation process.”

Dr. Bekir Tanriover

Assistant Professor of Internal Medicine, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center

Now or Later? Using @RISK to Evaluate Transplant Timing

Dr. Tanriover also used @RISK to answer another clinical question: what if the kidney in question is of adequate size, but its split function level (functional asymmetry between two donor kidneys) is well below what is considered acceptable for transplantation? “Would you still take that living kidney immediately, or would you instead wait to accept a kidney from a deceased donor at the expense of prolonged wait-time and possible increased risk of dying?” Dr. Tanriover asks. “Currently there is no standardized protocol on how to approach this decision.”

To answer this question, he conducted a sensitivity analysis with @RISK. In the model, he kept the size of the kidney at the transplant-worthy level, but varyied the functionality to 5%, 10%, 15%, etc. “We wanted to know what recipient outcomes would be in a year with these different levels of split kidney function,” says Dr. Tanriover. “How do you optimize outcomes, and what should be the limiting level of kidney transplant function?”

Running the simulation 10,000 times, Dr. Tanriover and his colleagues found that even with very low kidney function levels, there was only a small incremental risk of a recipient having less than ideal outcomes one year later.

“In our opinion, the risk of receiving a preemptive living renal transplant with any extreme split function difference, as long as adequate donor kidney volume is transplanted (2 ml/kg), outweighs the benefit of waiting for a deceased donor renal transplant that has higher function,” Dr. Tanriover writes in the study. “The reason for this is that the preemptive kidney transplantation offers lower mortality and allograft failure risk as compared with patients who received a transplant while on dialysis.”

With this probabilistically determined information, doctors now have a clear and simple answer to complicated clinical questions around kidney transplantation. “It’s clear that everything pretty much comes down to the size of the donor kidney—higher kidney volume equals better patient outcome,” says Dr. Tanriover. “It’s helpful to know that the split renal function test results and implantation kidney biopsies don’t add any necessary information in the overall big picture.”

Figure 2: Tornado chart showing predictors ranked by effect on patient outcome.

Key Benefit of Using @RISK: A Clear View of the Correlation between Variables

Dr. Tanriover says that one of the main benefits from @RISK was that it enabled him to extrapolate data from the initial 100 patients to get results from 10,000 simulations, which gave a much clearer picture of which kidney measurements mattered the most.

“What I found very useful and unique about @RISK is, nothing in the real world is independent—all variables are closely dependent on each other,” he says. “With @RISK, when I defined the distribution, I was able to put in the correlation between the variables, which got discounted in the outcome, and allowed me to see the real effect of each variable. It’s very powerful from that standpoint—it makes a real life example in situations where there’s just no way I could get data from 10,000 donors.”