What does it take to turn a classroom, a school, or a university from struggling to stable? Dr. Jonathon Saphier, Founder and President of Research for Better Teaching in Acton, Mass., has been investigating that question for more than 50 years – first as a classroom teacher, then as an instructional coach and consultant. He recently hosted a Lumivero webinar, 50 Years of Lessons on Leadership for Teacher Development: What Teachers and Higher Ed Administrators Can Learn, to share key insights about turning schools into professional learning communities where educators can grow alongside their students.

Sponsored by Lumivero’s Sonia and Tevera student management software solutions, this webinar offered actionable insights for school district and higher education administrators alike. Watch the webinar or continue reading for the highlights from Dr. Saphier’s presentation.

Understanding What Matters Most for Student Achievement

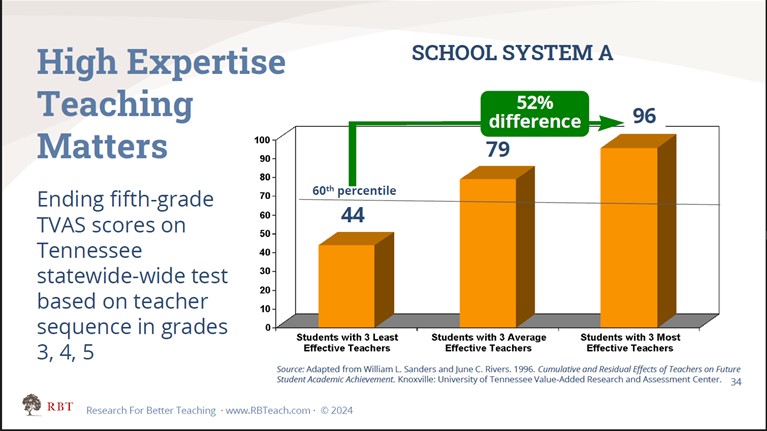

Starting off, Dr. Saphier presented evidence that demonstrated the impact skillful teaching has on student achievement.

“It’s well-known that the expertise of the individual teacher is the most powerful influence,” Dr. Saphier explained.

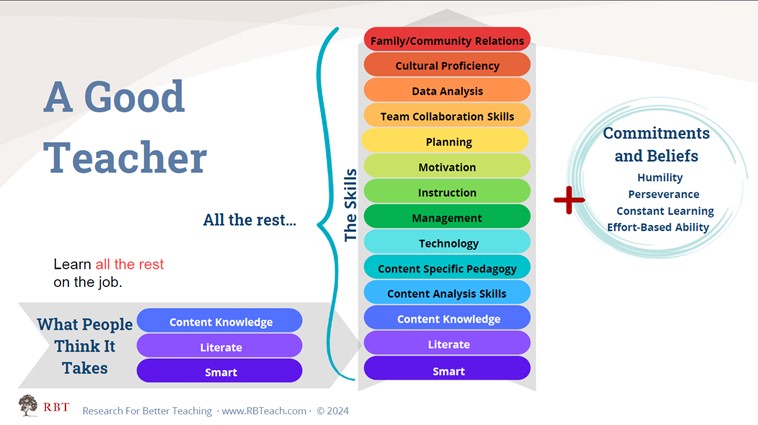

However, the knowledge base required for effective teaching is also broader and more complex than many people recognize – even people who are educational professionals. Skillful teaching is more about understanding the content area or innate intelligence. It requires a wide set of competencies spanning organizational management, the ability to motivate, cultural competence, and more. Dr. Saphier pointed out that most of this knowledge base is not acquired during training. Instead, it’s acquired on the job.

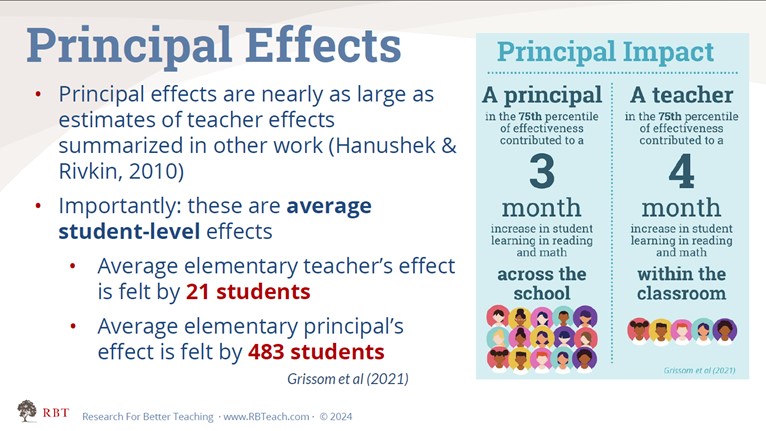

Teachers can’t effectively develop their knowledge base without support from their administrative leaders. Evidence shows that administrative leadership also matters when it comes to student learning and achievement. In fact, according to Dr. Saphier, “there's a multiplying effect going on” when educational leaders focus on empowering high-expertise instruction.

“If I improve as a teacher, I'm going to influence the kids I have in my room, but if I [as an administrator] get all the teachers in my building to improve, then I'm influencing all of the kids,” said Dr. Saphier.

A 2021 study on the impact of principal effectiveness commissioned by the Wallace Foundation supports this, estimating that while an improvement in teacher performance affects an average of 21 students, an improvement in principal performance impacts 438 students. The study states that “if a school district could invest in improving the performance of just one adult in a school building, investing in the principal is likely the most efficient way to affect student achievement.” (p. 34)

Dr. Saphier explained that this improvement isn’t needed in operational management. “I'm not talking about budgets . . . what I'm talking about is what [an administrator] does to influence the expertise of the teachers for teaching in their building,” said Dr. Saphier.

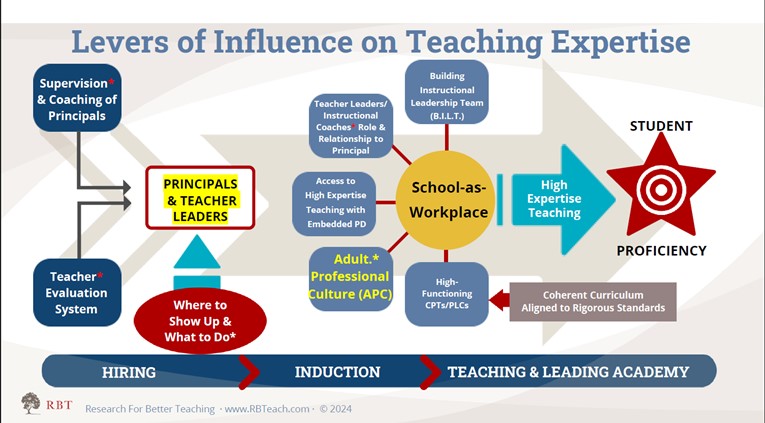

Redefining the Goal of Educational Leaders

Educational institutions at every level need to re-focus their priorities, explained Dr. Saphier. “We want to make every school a reliable engine for constant learning about high-expertise teaching.” When administrators see empowering high-quality teaching as their main role, they are really focusing on improving the single most important influence on student achievement. There are many levers of influence administrators can use to create an environment for effective teaching.

The first step administrators can take to support teachers is to create dedicated time and space for planning.

“When things are not going as we want them to in classroom, it often has an origin in the planning that went into the design of a lesson,” said Dr. Saphier.

Administrators need to schedule regular meetings for:

- Instructional planning at the building- or department-wide level

- Instructional planning at the grade or content level

The key is to ensure that high-level instructional planning is focused on making decisions for the entire school or department, instead of “the independent duchy of English or the republic of mathematics, as sometimes happens with secondary school leadership teams,” said Dr. Saphier. Working with an instructional adviser or coach, if available, can help guide this type of decision-making.

The next step for administrators is to ensure they are regularly observing teachers, both in the classroom and during prep time. However, observing and providing feedback are skills that require development, even for administrators who have teaching experience.

“Because one was an effective teacher doesn't mean that one knows how to . . . put into words and give evidence-based feedback about what it is that you have observed,” said Dr. Saphier. This is where embedded professional development matters.

Embedding Professional Development into Every Workday

Educators at all levels engage in professional development days throughout the year. However, Dr. Saphier points out that “the main place people get better at their teaching is their own . . . workplace.” Professional development that’s delivered via seasonal, one-off workshops isn’t enough, he argued. Anything learned during a workshop or in-service must be followed up by administrators, instructional coaches, and teachers so that professional development becomes embedded in the life of the school.

Dr. Saphier played a clip featuring Principal Tara Gagnon who was able to take her struggling school to a high-performing one by focusing on empowering teachers. She explained that one step she took was to attend professional development workshops with her teachers.

“You wouldn’t ask anybody to do anything you wouldn’t do yourself,” said Principal Gagnon. Engaging in professional development alongside teachers demonstrated her commitment to better instruction. “They see oh, I'm not just top-down making demands. I want to be part of this because I can't wait to see where this takes us.”

Attending workshops is not just about sending a signal. It also ensures that administrators really understand what teachers will be working toward implementing in their classrooms. They can then ensure the skills covered in the workshop are followed up through planning and observation.

“When [educators] see the leader willing to be a learner and willing to be in dialogue about how it's going,” Dr. Saphier said, “that leader is demonstrating the importance of professional development. It is also part of fostering an adult professional culture in the institution.”

Creating an Adult Professional Culture to Foster High-Expertise Teaching

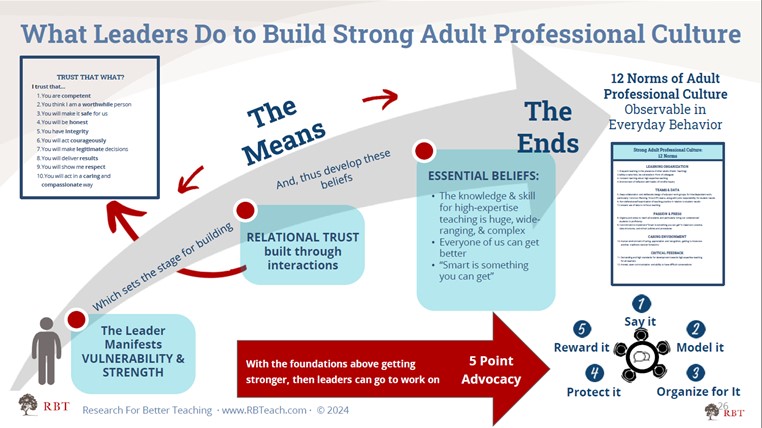

An adult professional culture is a workplace environment that fosters high performance through respect, constant learning, and interactions that build trust among colleagues. The foundation of a healthy adult professional culture is the attitude of the leader.

Over years of observing effective administrators and reviewing research findings, Dr. Saphier describes the ideal attitude as one of “vulnerable strength.” Leaders are vulnerable when they demonstrate that they, too, need to constantly learn and improve. They are strong when they consistently make decisions that empower constant learning and improvement.

Strong educational leaders make it possible for instructors to admit when they are stuck or struggling by ensuring that they will not be subject to sarcasm or harsh criticism. They foster deep collaboration among instructors that focuses on learning more about good teaching. They also encourage honest evaluation of student performance data to guide re-teaching and learning where necessary.

By consistently modeling a willingness to learn and improve, and by rewarding and acknowledging others who do the same, administrators gradually create a more open and collegial dynamic among teaching teams – in other words, an adult professional culture.

Skillful Use of Data for Assessment of Student Learning

Dr. Saphier’s focus during the webinar was on the importance of re-focusing educational institutions on empowering high-performance teaching. He briefly mentioned the importance of using data for instructional improvement, but skillful use of data is a major focus for his organization.

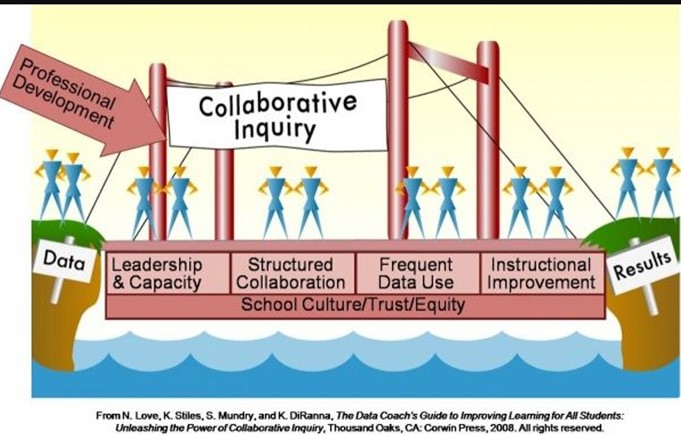

On the Research for Better Teaching website, he stresses that data must be used in an environment of collaborative inquiry about assessing student learning and where improvement is needed – not as a tool for punishing or micro-managing instructors. He then offers four steps for making skillful use of performance data for assessment of student learning and driving instructional improvement to help students.

These four steps include:

- Designating data coaches or teacher-leaders and building their capacity to work with colleagues to promote data and assessment literacy

- Setting up regular, structured team meetings to review and evaluate student data

- Encouraging teachers to analyze data frequently – for example, before, during, and after instructional units to better understand learning outcomes

- Making a commitment to improve teaching and learning based on data analysis

When deployed within a strong adult professional culture, student performance data can be an important tool for driving constant improvement in teaching at any level of education.

Interested in learning more about creating a culture that supports high-expertise teaching? Watch the complete webinar with Dr. Saphier.

Learn More About Data Tools for Assessing Student Learning

If you need help with using your data for formative and summative assessments to better support students, explore Lumivero’s solutions for educators! Sonia, a student placement software solution, and Tevera, an outcomes-based student assessment and field experience management platform, are designed to empower instructors and students while driving program improvement.