How the information literacy skills you learn in your studies can help

Amidst all the uncertainty of the current pandemic, one thing has become crystal clear: misinformation can spread as quickly as a virus. I’ve seen many posts on social media shared by friends about supposed cures or precautions one should take to avoid getting sick. While the information my friends shared was often benign – drink tea, eat more garlic, take steamy showers – many other supposed "cures" floating around the internet were not and even led to hospitalization in some cases. Fear can often cloud judgment, so it’s especially important in times of crisis, or an “infodemic” as the current situation has been called, to be able to identify misinformation and separate it from legitimate news or healthcare recommendations.

Fortunately, you get a chance to practice this skill every time you have to write a paper. It’s called information literacy, and you likely had some training in it in your first year of college or university. Information literacy basically just refers to how to find, work with, and judge the quality of information, and it’s an essential skill when you have a world of potential sources at your fingertips but want to locate the best, up-to-date, and highest-quality sources for the topic you’re writing about. If writing a paper is like building a house, you want to ensure that your sources – the foundation of your arguments – aren’t shaky.

Types of sources to use

So how do you find these sources? And how can you evaluate if they’re good or not? First, make life easier for yourself by not starting with a Google search, since you will end up having much more work when examining the quality of each source, and you’ll simply have to sift through too many bad sources. The backbone of any research you do should usually be comprised of academic sources, that is sources written by an expert in the field and ideally reviewed by another expert in their field, often in a peer review process. Most often, academic sources are either journal articles or books. To find them, use your library’s general search portal or search individual databases for journal articles and your library catalog for books.

Subject guides are an excellent place to continue your search. These are webpages that librarians or someone in your academic department has created with all of the top resources recommended for research in your discipline. Preferred databases vary a great deal by field, so these can really help if you’re new and don’t yet know which databases, websites, and books you should be using.

What about newspaper articles and other news reports?

While you’ll nearly always want to use scholarly books and articles for your papers, there are times when you will want to work with other types of sources. In past blog posts, we’ve already looked at some more problematic types of sources, such as Wikipedia and social media. But there’s one we haven’t covered yet: the news.

First, it’s important to remember that although media outlets often seem authoritative and objective, the articles, infographics, podcasts, and videos they produce are not academic sources. Articles are written by journalists, who are usually generalists and not specialists in the field they’re writing about. While most conscientious journalists will consult a few different experts for a story, what the experts say is still being filtered through the journalist and the short length of most news pieces can mean that some context gets lost. For these reasons, it’s a good idea to hunt down the research of the experts in question and interpret it for yourself when you’re writing a paper on the topic in question. Similar to how you might use Wikipedia and information found on social media, you’ll often want to use news articles as a jumping off point from which you can hunt down the sources or researchers mentioned rather than using them as a source in their own right.

However, news reports can also be valuable primary sources in certain cases. For example, if your paper is about an event in the past, you’ll need to rely on news articles or videos to get the reported facts or to put the event in the context of its time. You might also cite a news report for other reasons: if you’re examining people’s opinions, if you need evidence for trends, or if you’re doing research on a current political or cultural topic on which no academic literature exists yet.

Judging the quality of news

Unfortunately, we now live in the era of “fake news” in which it’s very easy for people to create or modify existing news articles, videos, and images. So-called “deepfake” videos in which one person’s face is replaced by another, can even make it seem as if a political leader or famous person is saying or doing something outrageous. But fake news doesn’t have to make use of the latest technology to be effective; sometimes the hardest to spot cases are the subtlest. For example, an image might simply be placed in a different context from that in which it originally appeared. Or an older news article published by a legitimate press might simply be given a new, incendiary title and posted to social media.

Luckily, there are now a number of organizations that do background checks on news that seems too good – or bad – to be true. Factcheck.org, Full Fact, and PolitiFact are just a few of the most well-known, but new regional ones are emerging all the time. These can be good places to verify whether what you’re reading is true or not, especially for a news story that’s gone viral.

Visual misinformation can sometimes be harder to pin down, but here too a lot of organizations are now working to fight back. The News Provenance Project has the aim of one day making it possible to track the source of an image using blockchain. In the meantime, you can use the Google reverse image search or TinEye to see where else, when, and in what context an image was already used.

Putting your information literacy skills to work

Although all these tools can be helpful, there will be many things you’ll still need to evaluate yourself. Fortunately, the basic checks you do to evaluate your other sources also apply to news reports. First, start with the bibliographic information or metadata you can find for the source. For instance, you will want to check if the work has an author, and if so, who the author is and if they might have any kind of agenda. You’ll also want to check whether the information is current or if it’s outdated. Check who the publisher is and whether the publication or website is known to be biased. If you’re using Citavi, remind yourself to do this check by assigning the Examine and assess task to all newly imported references.

Next, examine the content of the source. Does it use inflammatory language or express a clear bias? Are different viewpoints presented or is it one-sided? Are facts cited that you can double check – or is it just the author’s opinion? Are there any citations or links to the sources the author used? Does the headline match the content?

Sometimes if a source seems okay at first glance, even if its content is a little strange, it can be good to check in with yourself, too – have you really done your due diligence? Or did this content reflect your own views so you assumed it was fact? People are more likely to believe at face value information that aligns with their views and values. This is known as confirmation bias, and it’s an easy trap to fall into. I’ve fallen victim to it myself with the social media images of dolphins swimming in the Venice canals. Since it made sense to me that nature would rebound with less people polluting the environment, I accepted these images without question. Only later did I see that the photographs were actually not taken in Venice at all but far away off the coast of Sardinia.

To make evaluation easier, not just when writing a paper, but also in real life, there are a few different frameworks that you can use. IMVAIN is an easy-to-use acronym that can help you remember what to check: if a news report is independent, i.e. it’s not published by an organization that could be biased, if it uses multiple sources, if the information can be verified, if the source is authoritative and/or informed, and if the source is named, i.e. if an author is given. More information and practice exercises from Stony Brook University’s Center for News Literacy can be found here.

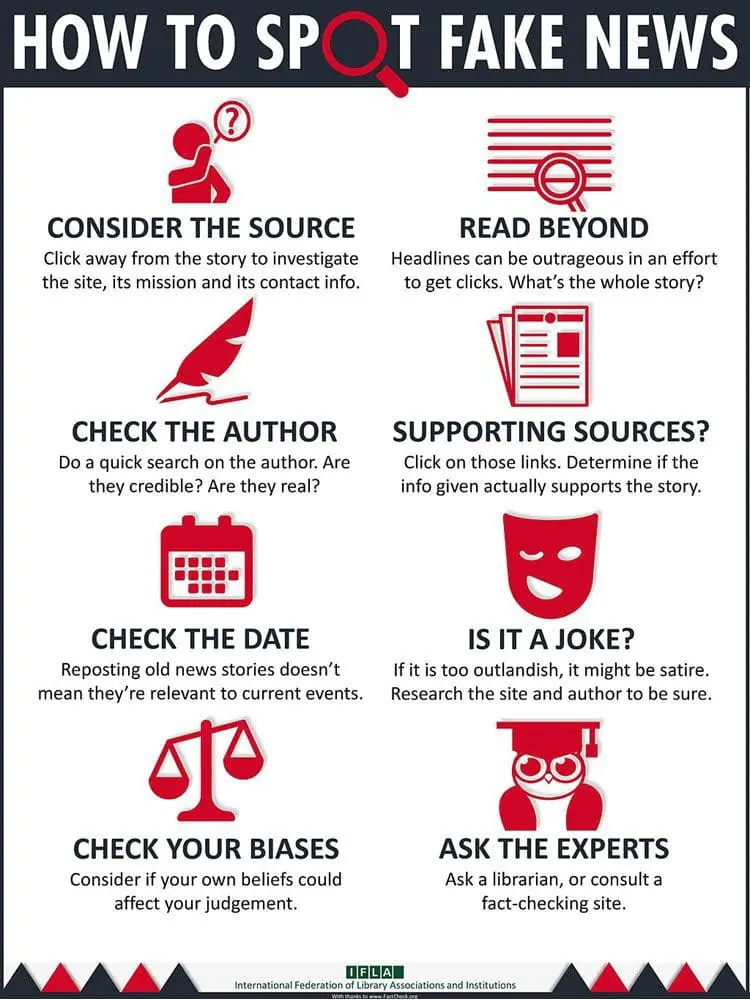

The International Federation of Library Associations (IFLA) also offers a helpful graphic, which we’ve shared below:

They are currently even offering a modified version for how to spot fake COVID-19 news:

All too often it can seem that what is learned at college or university is irrelevant to “real life”, but that’s not the case with information literacy. Getting better at evaluating sources will help you not only during your studies, but also in your day-to-day life.

Was there ever a time you were tricked by a “fake news” article, image, or video? Are there other methods you would recommend for verifying whether news is legitimate or not? We’d love to hear some of your suggestions on our Facebook page!

About Jennifer Schultz

Jennifer Schultz is the sole American team member at Citavi, but her colleagues don’t hold that against her (usually). Supporting research interests her so much that she got a degree in it, but she also likes learning difficult languages, being out in nature, and having her nose in a book.