The Australian Department of Climate Change commissioned AECOM, a professional technical and management support company, to evaluate the risk and costs of climate-change-related flooding of the Narrabeen Lagoon. The lagoon is near Sydney, a populated region that is particularly vulnerable to flooding damage. Using @RISK to run Monte Carlo simulation and optimization techniques on their analysis, AECOM was able to estimate the social benefits of adaptation to climate change in terms of willingness to pay, rather than just costs avoided. Using @RISK, they generated more realistic probabilities of overall costs and benefits, and modeling the expected future values of variables such as rainfall.

Climate Change to Affect Australians

Businesses around the globe will face significant economic risks from climate change, such as fluctuations in the availability of resources, supply and demand for products and services, and the performance of physical assets. The frequency and intensity of extreme weather events and natural disasters has and will continue to increase, resulting in significant economic and human losses. Damages from floods, cyclones, bushfires and drought already cost local economies millions of dollars. For example, in Australia, the estimated gross domestic product was reduced by 0.5 per cent due to the Queensland floods of 2010–11, and the Victorian bushfires of 2009 (commonly referred to as ‘Black Saturday’) cost more than $4 billion and resulted in the deaths of 173 people.

Narrabeen Lagoon – located in the northern suburbs of Sydney, Australia – is an area which is already subject to flooding. When the Narrabeen lagoon’s entrance is blocked, it can fill like a bathtub, thus flooding the surrounding land and houses. The community can tackle this problem in various ways, including lagoon entrance opening, levee construction, flood awareness, and planning control. Under various climate change models, the frequency and severity of weather events is expected to increase going forward. Because climate change is expected to increase flooding in the Narrabeen catchment over the coming century, decision makers needed a clearer understanding of the different possible adaptation measures.

AECOM was asked by the Australian Department of Climate Change to conduct an economic analysis of climate change impacts on infrastructure. The objective of the study was to use an economic cost-benefit analysis to identify both what measures Government should invest in to prevent impacts from flood events and when they should invest. Measures ranged from policy, planning thorough to infrastructure (e.g. elevating new houses and levees).

“The objective of the study was to use an economic cost-benefit analysis to identify both what measures Government should invest in to prevent the impacts from flood events and when they should invest,” says Robert Kinghorn, who, along with Lisa Crowley, previously worked on the project as economists at AECOM. “Measures ranged from policy, planning thorough to infrastructure (e.g. elevating new houses and levees).”

Robert Kinghorn

AECOM

Conducting the Evaluation

To conduct the analysis, Kinghorn and colleagues had to synthesize large datasets using @RISK. “The number of permutations and combinations of possible outcomes was very large,” says Kinghorn. Three significant data sets were applied. Different combinations of flooding events over a 90-year period were combined with 10 different climate change models. This provided a forecast of different flooding events over time, in terms a variation in frequency and intensity.

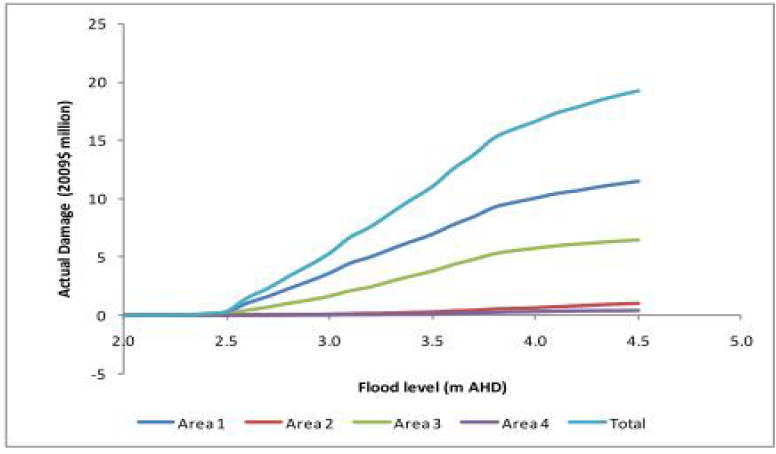

Example of residential damage cost profile at different flood heights.

“We also had six possible adaptation measures,” Kinghorn explains. “These could be introduced at any time over the 90-year period and in some cases could be different scales. For example, it may only be worth investing in a levee which is 2.5m high rather than 3m high, as the probability of a higher flood event is sufficiently low as to not to justify the additional expenditure…This then helped us develop a portfolio of adaptation measures and the approximate timing as to when they should be introduced, so as to maximise the Net Present Value of adaptation,” says Kinghorn.

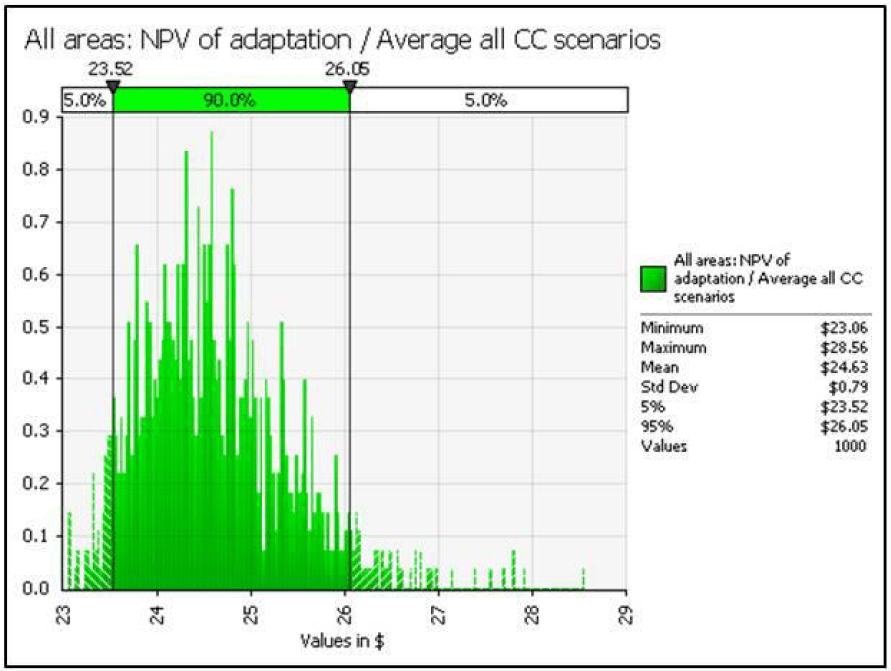

Optimised NPV for all adaptations.

This timing of the measures was of particular interest to decision makers in the Australian Government. The analysis showed that the benefits of some of the cheaper measures, such as the planning controls, were so great that they should be instituted immediately. However, the analysis showed that investment in some of the more expensive infrastructure measures (such as levees) wasn’t warranted immediately, and would best be deferred for a number of years. It was found that in the near term the avoidable cost of the floods would not outweigh the capital cost of the infrastructure.

“Whilst our analysis found that Government would be better off deferring capital investment in the short term; provisions can be made for this in the future,” Kinghorn says. “For instance, acquiring land that enables the adaptation option to be undertaken at some point in the future. This is known as real options analysis – rather than committing major capital expenditure, government and business can take an incremental approach by making small investments in the near term and only committing large expenditure when there is greater certainty that the investment is warranted.”

@RISK allowed Kinghorn and his colleagues to provide the Australian Department of Climate Change with a clear understanding of the cost and benefit trade-offs. “The benefit of this approach is that it avoids the opportunity cost of early or no investment, while empowering decision makers to determine the options (i.e. pathways) that are the most suitable for adapting to climate change at a given point in time,” says Kinghorn.