Researchers at the University of California San Diego School of Medicine used @RISK and PrecisionTree to create a more effective and nuanced screening program for the Hepatitis B virus in Asian populations in their region. In some communities, the rate of Hepatitis B infection can be as high as 16-18%. The models and decision trees created using Lumivero software, previously Palisade, helped the scientists determine which type of screening test to administer, and what location was most effective (e.g. health clinic versus community event), when considering widely different segments of the Asian immigrant population. This information has informed both San Diego County and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force in their public health policy approaches.

A Devastating Disease

The Hepatitis B virus is 100 times more infectious than HIV, and kills more than 780,000 people each year. It can cause a potentially life-threatening liver infection often leading to cirrhosis and liver cancer. “It’s really a devastating disease,” says Dr. John Fontanesi, Director of the Center for Management Science in Health at University of California San Diego School of Medicine and part of a team of investigators exploring better ways to both prevent and treat Hepatitis B and C. It’s also preventable with a series of vaccinations and, if caught early, can be managed much like other chronic diseases with appropriate drugs--letting those treated lead normal productive lives.

The virus seems a perfect candidate for a widespread screening program. However, Dr. Fontanesi explains this hasn’t been the case. “The U.S. Preventative Services Task Force has spent over 30 years investigating the societal cost-benefits of universal Hepatitis B screening, and to date the studies indicate such screening just isn’t worth it.”

Dr. Fontanesi and the study team led by Dr. Robert Gish, M.D., however, took a more nuanced view of the issue. After dedicated field work and the help of @RISK modeling, the researchers arrived at some entirely different findings that now have the U.S. Preventative Services Task Force (USPSTF) re-tooling their Hepatitis B screening recommendations.

Public Health Policy: One-Size Does Not Fit All

If one considers the U.S. population as a whole, its rate of Hepatitis B infection is “less than a half percent,” says Dr. Fontanesi, a statistic that factored into the USPSTF’s initial decision against widespread screening. However, “Hep B isn’t evenly distributed across all ethnicities and races,” says Dr. Fontanesi. “While it’s very low in Europeans, the rate is as high as 16-18% in Asians.” Indeed, according to the CDC, Asian and Pacific Islanders account for more than 50% of Americans living with chronic Hepatitis B. The disease is particularly prevalent in Asian immigrant populations. Thus, while screening the entire American population does not yield enough benefits to outweigh the costs, the math changes if one considers screening this particular ethnic group.

But how best to screen this population? “All Asians’ isn’t a meaningful term,” explains Dr. Fontanesi. “Using San Diego as an example, there are two very different Asian immigrant populations,” he says. One is made up of university students, post docs and faculty and professionals with relatively high socioeconomic status; the other is made up of Laotian and Hmong and Vietnamese immigrants who tend to have lower socioeconomic status. “The only thing they really have in common is their susceptibility to Hepatitis B.” Given how different the income levels and likelihood of having health insurance and access to care are between these two populations, “we thought why not fit screenings to the specific population?” says Dr. Fontanesi.

Selecting Different Screening Methods

The team examined two different variables in their screening efforts: the kind of test performed, and where it is conducted. They examined two different kinds of tests: standard care testing, and point-of-care testing. Standard care testing involves taking a blood sample, typically at a clinic, processing that sample at a lab, and waiting two weeks to get highly accurate results. Point-of-care testing occurs at the site of patient care, wherever that may be, and results--while less accurate and comprehensive--are available in 15-20 minutes.

The team also examined the location of testing—either a doctor’s office or clinic, or at community events where groups of Asian immigrants would gather, such as festivals or celebrations, that were used as opportunities for outreach and testing.

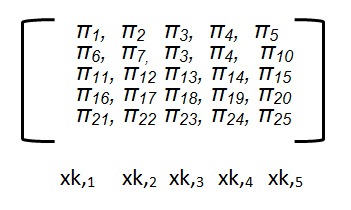

“We looked at these two axes—point of care versus standard care, and community event versus doctor’s offices, and looked at the number of people tested, the likelihood of someone testing positive, and how hard it is to get ahold of them for follow-up treatment or vaccination,” says Dr. Fontanesi. “As you can imagine, that’s a lot of conditions or states, so we used @RISK to build a Markov model in order to determine which of these efforts were worthwhile to do.”

Markov models are stochastic simulations in which the probability of each event depends only on the state of the event before it. The five major possible mutually exclusive “states” are expressed as:

- xk;1 Unexposed

- xk;2 Immune

- xk;3 HBV Acute infection

- xk;4 HBV Chronic infection

- xk;5 HBV- Liver Disease

- xk;6 HBV- Related death

@RISK Results and Real-World Applications

After running the simulation in @RISK and reviewing the results in PrecisionTree, the team had a list of possible outcomes, demonstrating the significant impact that small changes in early detection rates can make in both costs and lives saved. Dr. Fontanesi and his team converted these outcomes into a set of questions that could be used to decide what the best method of screening is for a given community.

The results from the model showed that for the San Diego Area, wealthier, more educated Asian immigrant populations were better served by Standard of Care testing conducted in their doctor’s office; it allowed for better continuity of care, referral to specialists, and long-term health savings. For poorer immigrant populations, point-of-care tests held at community events yielded better results, as many individuals in those groups were difficult to get ahold of for follow-up on test results and treatment.

This information proved so valuable that San Diego County incorporated it into a Geographic Information System (GIS) which superimposes over census information on the local populations, along with socioeconomic status and likelihood of using public or private transportation. “This information has allowed them to be really focused on targeting whether they’re going to be doing standard of care or point of care testing, and if they’ll do testing in the community or in a clinic,” says Dr. Fontanesi. “So we were able to help them match the screening policy to the community, rather than use a standard public health approach.”

The information has also informed the USPSTF in reassessing their policy towards Hepatitis B screening. They are currently re-writing their recommendation to include targeted screening of certain Asian communities and populations, thanks to Dr. Fontanesi’s findings.

The Benefits of @RISK

Dr. Fontanesi says that @RISK was integral to his study’s nuanced approach. “In research, we tend to state problems monolithically—‘is this good or not’—but most of life is not that clear cut,” he says. “Much of life is, ‘it depends’, and we were able to use @RISK to quantify ‘it depends’, to tell us what it actually means when we say that.” He adds that @RISK’s graphical visuals were an invaluable feature as well. “When you’re trying to communicate statistics to the medical community, people can get lost, but if you show them @RISK, they get it instantly; that visual representation is so much more powerful than written text or a table of numbers.”

Originally published: Oct. 7, 2022

Updated: June 7, 2024