Recorded interviews are one of the most popular forms of qualitative data collection. They are nearly always transcribed, and the analysis is conducted on the transcribed text. But is that enough? What is the path forward with the transcription process? Let’s discuss the different approaches to transcription, analyzing the text, and making transcription go beyond just words.

What Is Transcription?

Transcription involves the transformation of an audio or video file into text. Qualitative researchers often find themselves transcribing interviews or focus groups as part of their research initiatives. But what happens after the transcription is complete can vary. As Christina Davidson (2009) states, not enough attention has been given to transcription in qualitative research as evidenced by:

- the lack of empirical accounts of transcription,

- not enough attention given to the problematic nature of transcription in research reports and

- the lack of training of researchers.

According to Judith Lapadat (2000) the implication of this transformation depends on where the researcher stands “on the paradigmatic continuum from positivism to interpretivism” (p.207).

Transcription Means Different Things To Different People

As transcription is helpful in a wide variety of sectors such as academic, commercial, government, and non-profit, it can hold different meanings to different researchers.

1. Positivists see transcription as a manual task – unrelated to analysis

According to Lapadat (2000), for positivists, transcription is seen as mainly unproblematic – the verbatim transcript is a one-to-one match with the spoken word and that spoken word is the observable event and the job of the transcriber is to accurately and completely capture the spoken word. The transcription is just a manual task. So in answer to the question, why do we transcribe, positivists would argue that it is to transform spoken data as written data which can then be analyzed.

2. Interpretivists rely on critical reflection

However, interpretivists have a different view of transcription. Unlike positivists, they do not see transcripts as neutral representations of ‘reality’. For them, transcripts are theoretical constructions. Talk is situated (Edwards, 1991) – people don’t talk in isolation. What is said is influenced by the context – who is in the conversation, where the conversation takes place etc. In an interview, the interviewee will position themselves with a particular identity. Interpretivists argue that you cannot strip the context from a transcript. Instead, interpretivists rely on critical reflection. Their answer to why would you transcribe is to start a process of reviewing and reflecting on the data.

3. The muddle in the middle

Lapadat (2000) also argues that there is a third approach which she calls ‘the muddle in the middle’. Different researchers have dealt with the challenge of transcribing in different ways. They might adopt a standard of transcribing without reflection or make up transcribing conventions as they go along. Lapadat (2000) sees this as a risky strategy as she argues that ‘transcription decisions both reflect the researcher’s theory and constrains theorizing’.

What Should You Transcribe?

Transcription should be related to your purpose. You may be interested in just the content of an interviewee’s story. Or you may be interested in how she tells her story – her emotions, what she glosses over, what she is not saying. Or you may be interested in her underlying motivation for telling her story. You should consider your purpose and approach to analysis before transcribing. For your purpose, you may just need to turn the spoken words into text.

There’s More To Transcripts Than Text

But textual information is just one component. Facial expressions and body movements give more information to form an interpretation. However, this information is stripped out of an audio file and hence lost. However, sounds such as laughter and sighs, the tone of the voice, length of pauses are picked up by the audio file and enriches the interpretation. These non-verbal aspects are critical for certain types of approaches to analysis – such as conversational and discourse analysis.

Conversational analysis has developed its own notation system to capture these non-verbal aspects as well as overlaps and interruptions in a conversation. But these non-verbal cues can be important in other forms of analysis as well – in order to form an appropriate interpretation of the spoken word. In addition, silences may need to be considered and interpreted.

The Four Layers of Transcripts: Contextual, Embodied, Non-verbal and Verbal

So, getting from the spoken word to the transcript can be seen as a process consisting of several layers. There is the contextual layer consisting of the environment where the interaction took place, there is the embodied layer consisting of the facial expressions and bodily movements. These two layers are stripped out of an audio recording but are available in a video recording. Then there are the non-verbal sounds and silences which are captured by the audio and finally the words themselves.

But which layer or layers you focus on depends on your purpose in the analysis. Ideally, the researcher should see transcription as part of the analysis process. And by repeated listening to the audio the researcher can get more immersed in the analysis. Check out the webinar below to learn more about how to use transcription as part of your data analysis process.

Available Options For Transcription

Transcription is a complex process. In the past, there were few technical options open to researchers, but more have become available over time.

Simple word processing: Divorced and manual

It is possible to play the audio and transcribe in Word, however, it is an awkward process – having to go back and forth between two software applications. The words are not linked to the audio and it is difficult to include timestamps. You will also need to think about the best way to format your Word document to capture what you need. This results with a transcript divorced from its original media.

Outsourcing: Costly and loss of control

The researcher outsources the transcription. While it might be useful if you have a lot of transcripts, the disadvantage is it is costly and you will lose control over how it is interpreted by the transcriber. There is no link between the spoken word and the transcript. And there will be delays with getting the transcript back.

Most transcription software still requires researcher transcribing

They could use transcription software such as F4. This is an improvement on working in Word and the audio file. The researcher is only working within one software package, timestamps are added by the software and the audio is linked to the text. However, the researcher still needs to transcribe word for word.

Dictation software is repetitious and original data is lost

Researchers can use dictation software such as Dragon Speak. However, they will have to listen to the audio and repeat what they hear. The disadvantage is that it is the researcher’s voice and intonations, pauses etc. that are captured, so the original tone, hesitations, and such are lost.

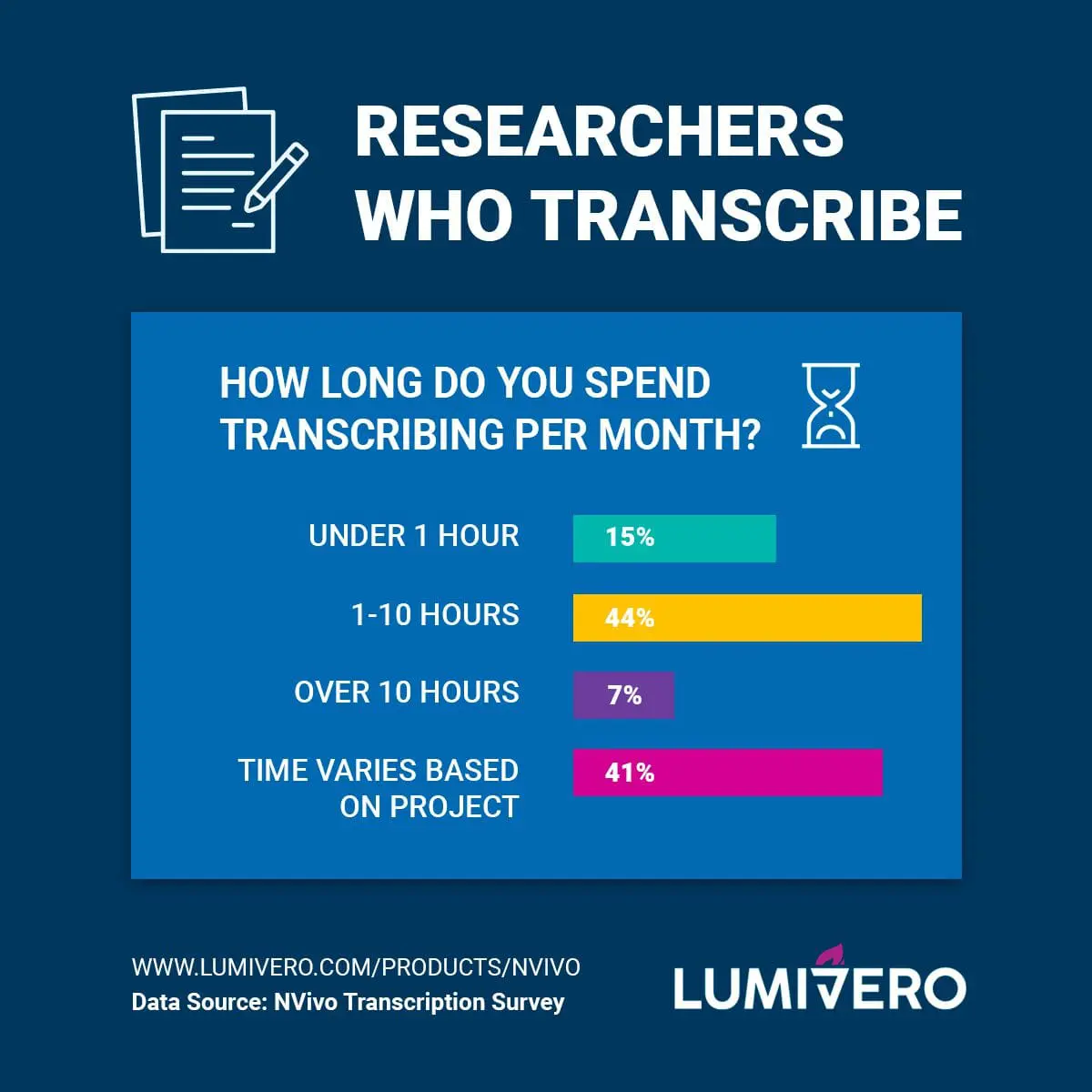

Introducing NVivo Transcription

Over time, technology has developed to support the transcription process. The latest development is to use transcription software with automatic speech recognition – such as NVivo Transcription. NVivo Transcription generates verbatim transcription with 90% accuracy from quality video and audio recordings by using natural language processing. With support for audio and video files up to 4hrs or 4GB and 42 languages, NVivo Transcription can support researchers around the world.

Not only can the original media and the transcript be viewed simultaneously but artificial intelligence helps with giving you an initial draft of the words.

Using NVivo Transcription

NVivo Transcription is fast

NVivo Transcription has a quick turnaround. You simply upload the transcript into your own (or your institution’s) account in the cloud. It takes half the time of the audio/video file for it to be ready. So, a one-hour interview will be transcribed in 30 minutes.

You control the transcript structure

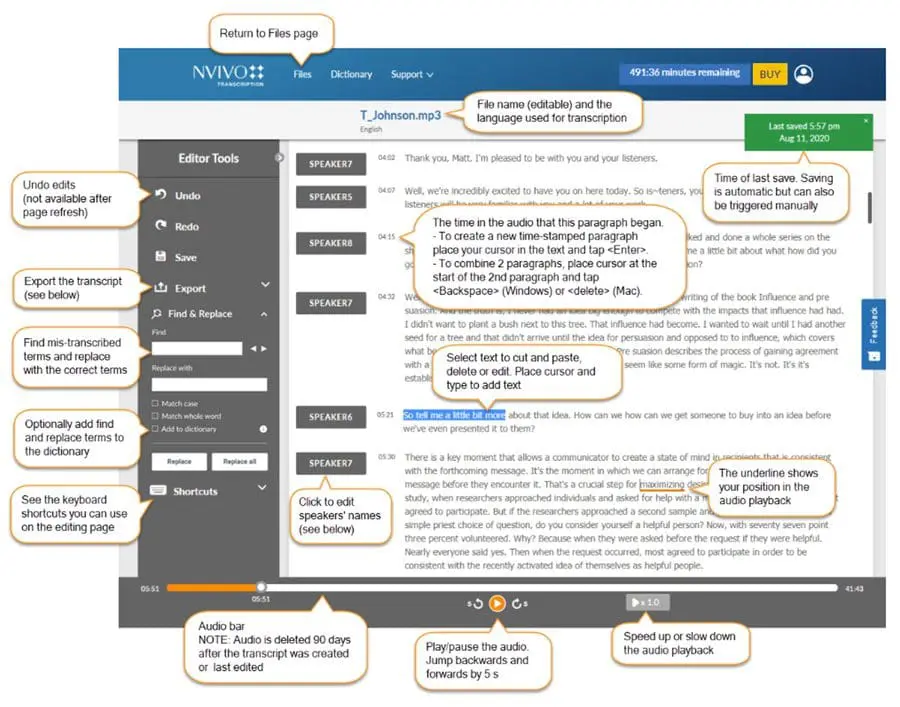

Each written word is linked to the spoken word in the audio file. While the words are transcribed, you can play back and hear not only the words but all the non-verbals. Bear in mind that people do not talk in sentences – so you will have control on breaking up the text the way you want in the editor. While the editor is structured with a column for speaker, you do not have to structure the transcript by turn, if that does not suit your purpose. You have control over altering the structure of the transcript.

Add screenshot of editor:

Simple imports for rich analysis

If you have NVivo, you can import the transcribed file directly in NVivo linked to its audio or video – so you can then do the rest of the analysis in NVivo with the text and audio/video linked in one file. Within NVivo you have the option to code or comment on just the media file or just the transcript or both. You will be able to add contextual interpretation to your data. (You also have the ability to download the time-stamped transcript into Word.)

It’s secure and private

Data security and privacy are top priorities for Lumivero. NVivo Transcription data is encrypted both in transit and at rest and only the account owner has access to and control over their data. Lumivero uses Microsoft Azure cloud services hosted in the EU. This is fully GDPR compliant. Additionally, NVivo Transcription is HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act 1996) compliant. HIPAA sets the standard for health data protection and Lumivero has the administrative, physical and technical safeguards in place to ensure compliance with the regulations and conditions set forth in HIPAA.

Lumivero uses Microsoft Azure public cloud hosted in the EU. This is fully GDPR compliant.

References

Davidson, Christina (2009) Transcription: Imperatives for Qualitative Research, International Journal for Qualitative Methods, vol 8. No. 2, pp. 35-52

Edwards, D. (1991) Categories are for talking: On the cognitive and discursive bases of categorization. Theory & Psychology, 1, 515—54

Lapadat, Judith (2000) Problematizing transcription: purpose, paradigm and quality, International Journal of Social Research Methodology, vol 3. No. 3, pp. 203-219

Editor’s Note: This post was first published in August 2019 and was updated in February 2022 and March 2025 for accuracy.

Silvana di Gregorio

Silvana di Gregorio

Silvana is a sociologist and a methodologist specializing in qualitative data analysis. She writes and consults on social science qualitative data analysis research, particularly in the use of software to support the analysis. She is also Lumivero's Product Research Director.