Inductive content analysis (ICA) is a qualitative research method used to identify themes from textual data without a predetermined coding framework, ideal for exploratory or policy-oriented studies.

This guide covers:

If you’re working with qualitative data and are not planning to use a predefined coding framework, inductive content analysis (ICA) can be a powerful way to uncover insights from your data. However, like many qualitative methods, the process can seem intimidating and time-consuming without clear guidance–especially for researchers new to this approach.

So, what does the ICA process actually involve—and how can you tell if it’s the right approach for your project?

In a Lumivero webinar on the subject, Professor Lynn Gillam and Associate Professor Danya Vears presented a clear, step-by-step walkthrough of how ICA works, when to use it, and how to distinguish it from related methods like thematic analysis. Their walkthrough was grounded in real experience, drawing from their work with students and colleagues who had found inconsistent terminology and vague definitions in the existing literature.

Keep reading for a practical look at how ICA works, or watch the full session on demand.

ICA is a qualitative research method for analyzing data such as interview transcripts, documents, or open-ended survey responses. The goal is to produce a summary of the content across multiple texts by identifying and categorizing recurring ideas. This methodology is frequently recommended for researchers working with textual data who are not applying a predefined coding framework.

There are two key features of an inductive qualitative content analysis process—it's both inductive and iterative. “The inductive bit is important,” Gillam explained, emphasizing that researchers don’t start with a rigid coding scheme but instead let the categories emerge from the data. “The other key feature is that it’s iterative. . . you end up with a final coding scheme that will be somewhat different from where you started.”

ICA focuses on manifest content—ideas that are easily observable in the text. While interpretation is always part of the process, manifest content analysis remains closer to the surface level meaning of what participants say. For those new to qualitative research, it's recommended to focus on manifest content rather than latent content, which involves deeper interpretation and aims to uncover underlying meanings not explicitly stated. An extreme example of latent analysis might be trying to interpret someone’s dreams.

In contrast to deductive analysis (where codes are predetermined and applied to the data), ICA is typically used when researchers are addressing an under-researched topic or responding to a practical or policy-driven question. It’s especially useful in health research, where studies are often smaller-scale, exploratory, and rooted in real-world complexity.

While ICA and thematic analysis share similar coding techniques, they differ in purpose and outcome.

“When your research is relevant to practice or policy and you're looking for practical outcomes, then inductive content analysis is a particularly useful tool for analysis because it speaks to the aims of your project and the needs of the audience that you're writing for,” said Gillam.

ICA is not used when a fully developed theoretical framework can be applied to the data from the start. In those cases, a deductive content analysis would be more appropriate.

The first step is to define a clear research question. This helps determine whether ICA is the right approach and guides the identification of meaningful content. Researchers need to be clear about what they’re looking for in the data—but without relying on a predefined list of concepts.

Although the research inevitably has prior knowledge of the literature on the topics, this doesn’t mean the analysis is deductive. The key is to remain open to new insights emerging from the data, rather than coding only what you expect to find. Openness is a key component of inductive analysis: researchers should endeavor to enter the coding process without fixed notions or presumptions, allowing categories to surface organically, whether they contextualize or challenge previous scholarship.

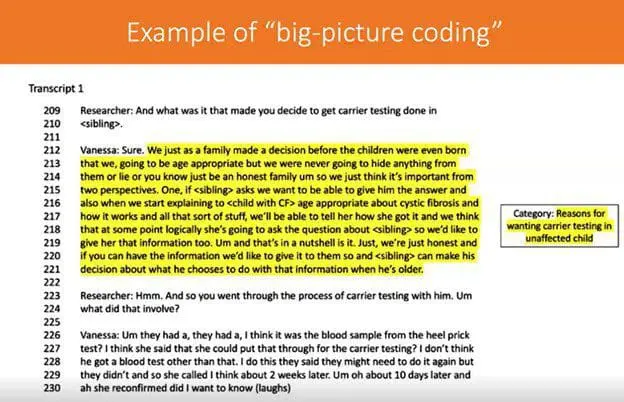

Next is the initial coding process. This involves reading through transcripts and identifying large segments that convey a clear idea, which are then labeled with broad content categories to help identify patterns. “You're basically coding big chunks of text that each have a meaning unit,” Associate Professor Vears said. “Sometimes a big chunk of text will have multiple meaning units. And that's okay. It's good to code it multiple times.”

These initial categories may reflect the structure of the interview questions, especially in studies using semi-structured interviews. However, ICA remains open to new themes emerging from participants’ responses.

ICA is not a linear methodology. After the first round of coding, researchers return to the data to refine and expand their codes. In the second round, the focus shifts to more detailed analysis, where codes become more specific and subcategories begin to form. It’s expected that things are going to change as you continue analyzing the data.

In some cases, a single subcategory may need to be further subdivided. In others, two categories may be merged. Given this, the coding schema should be updated throughout the process as new insights emerge. These categories often become the basis for the structure of the final results section.

ICA can be done by a single researcher, but many research teams include multiple researchers and coders. Co-coding is not about measuring agreement between coders in a statistical sense. Instead, it helps build shared understanding and introduces various perspectives into the analysis.

“Ultimately, it actually really helps enrich the data analysis,” Associate Professor Vears said. “Because you’ve got multiple people looking at it and through their own lenses. . . you’re going to get a more enriched and detailed understanding about the data because you’ve got multiple perspectives.”

The co-coding process begins with clarifying who will be involved, how many transcripts each person will code, and how overlap and differences will be managed. After individual rounds of coding, researchers meet to compare and discuss their interpretations and finalize a shared coding schema.

Once categories and subcategories are in place, the next step is interpretation. ICA does not require researchers to link their results to theory, though doing so is possible. Interpretation in ICA aims to explain what the data show, based on the categories developed during analysis.

“It’s very tempting to kind of ‘smooth things over’ or leave things out that are not really congruent with the rest of the story,” Associate Professor Vears said. “But actually, it’s really important not to lose that nuance by tidying things up.”

Researchers may choose to apply theory in interpreting the outcomes of ICA. For example, while studying views about genetic carrier testing of children, Associate Professor Vears shared that she used the concept of the “zone of parental discretion” after her initial ICA findings to interpret parents’ views on carrier testing for their children. This was done after inductive coding had been completed in order to provide a deeper understanding of the data.

Inductive content analysis can be both intuitive and insightful—but without the right tools, the process can quickly become overwhelming. Whether you're conducting a basic content analysis or complex, mixed methods research, having software that supports your workflow makes all the difference.

Lumivero’s research software is designed to support both inductive and deductive approaches to qualitative research—helping you stay organized, work efficiently, and gain deeper insights from your data.