Risk attitude—the mindset shaping how people perceive and respond to uncertainty—can quietly derail data-driven decisions and shut down promising opportunities. Clear definitions of uncertainty, probability, variability, and risk, along with the use of certain equivalents (CE), help improve decision quality. Aligning incentives to reflect a corporate, not personal, risk posture is essential to avoid value-destroying caution.

Most organizations think they’re making rational, data-driven decisions—but risk attitude often tells a different story. Whether it’s excessive caution or reckless optimism, the way leaders feel about risk can quietly steer choices, derail strategies, and shut down promising opportunities before they even get a chance.

It’s the mindset that shapes how people perceive and respond to the possible consequences of uncertainty—and it isn’t negligible. It has real consequences for business outcomes.

In a Lumivero webinar, Steve Begg, Emeritus Professor at the University of Adelaide, broke down why understanding and managing risk attitude is essential for improving the quality of our decisions. This is crucial because decision quality is the only control we have on outcomes—what actually happens depends on things we cannot control: other people’s decisions, “nature”, chance, etc.

Continue reading to explore the key insights from his presentation or watch the webinar on-demand.

Many decision-makers often have an imprecise understanding of risk management concepts, and important nuances in the differences between them. These misunderstandings can lead to lower-quality decisions, hence less desirable outcomes, or missed opportunities for better ones.

Clarity in the understanding and definition of these concepts is essential. Consistent language is how teams communicate risk effectively—without it, the quality of decisions can suffer. Misunderstanding these concepts doesn’t just create communication gaps; it can distort how risks are perceived, evaluated, and ultimately acted upon.

“Understanding a concept and using a consistent word to describe that concept [is] how we transfer information,” explained Prof. Begg.

Correctly assigning probabilities requires:

As a decision maker, you’ll also need to determine the following when considering risks:

Uncertainty can have both positive and negative outcomes, in a relative sense. Many organizations only focus on managing the negative ones. Professor Begg argues that this can be counterproductive.

“If you always look at the [negative] side of uncertainty,” he said, “you're taking a biased approach to your evaluation. And I can tell you any sort of bias, no matter what the nature of it, will lead you to lower long-run outcomes compared to being unbiased.”

Focusing on the negative outcomes, while understandable, can lead to missed opportunities. Considering the possibility of positive outcomes as well as negative outcomes can encourage a less limiting attitude toward uncertainty.

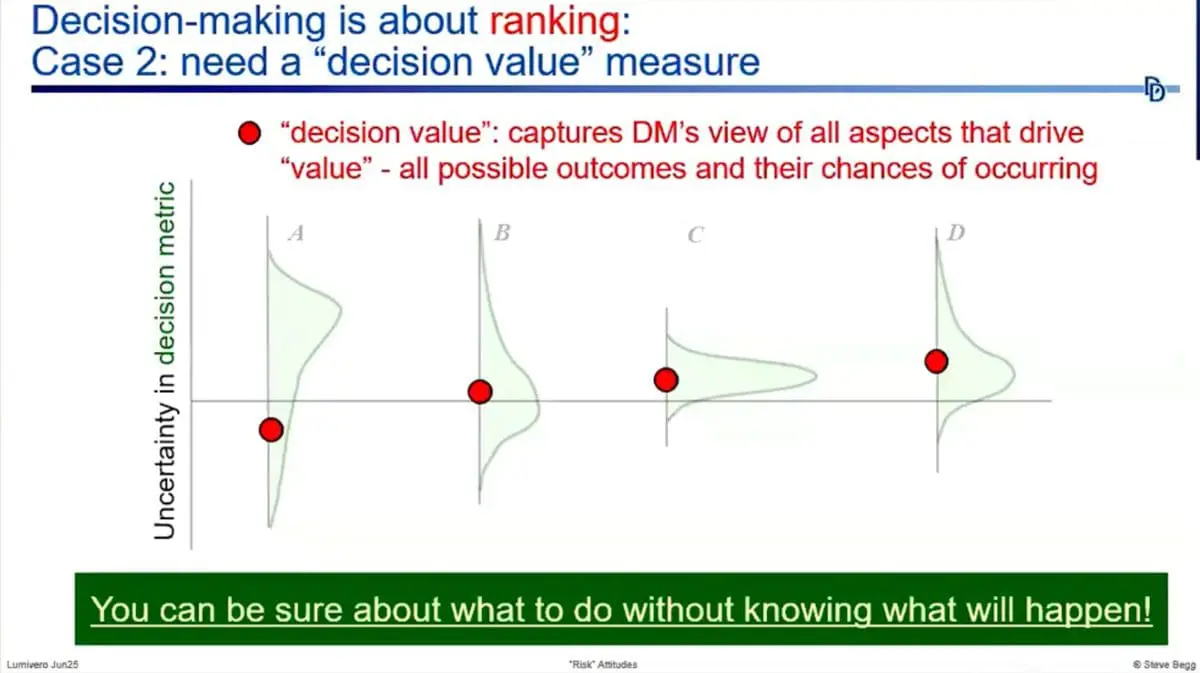

It is important for decision makers within organizations to understand that it is possible to identify the best decision option without eliminating or reducing uncertainty. That’s because deciding is really about ranking the available options to choose the best—and you can do that even if the options have uncertain outcomes.

Decision-making is about ranking – identifying the best decision alternative (A, B, C, D).

Where do the uncertainty (probability) distributions of each option come from? Often from a predictive model whose inputs are uncertain. Decision-makers, or their analysts, could assign probabilities to the uncertainty in the model inputs and run a Monte Carlo simulation with @RISK to generate the probability distribution for the key decision metric.

Focusing on uncertainty reduction can be more of an exercise in “spending corporate resources to feel psychologically comfortable than in adding insight to choosing the best option,” according to Professor Begg.

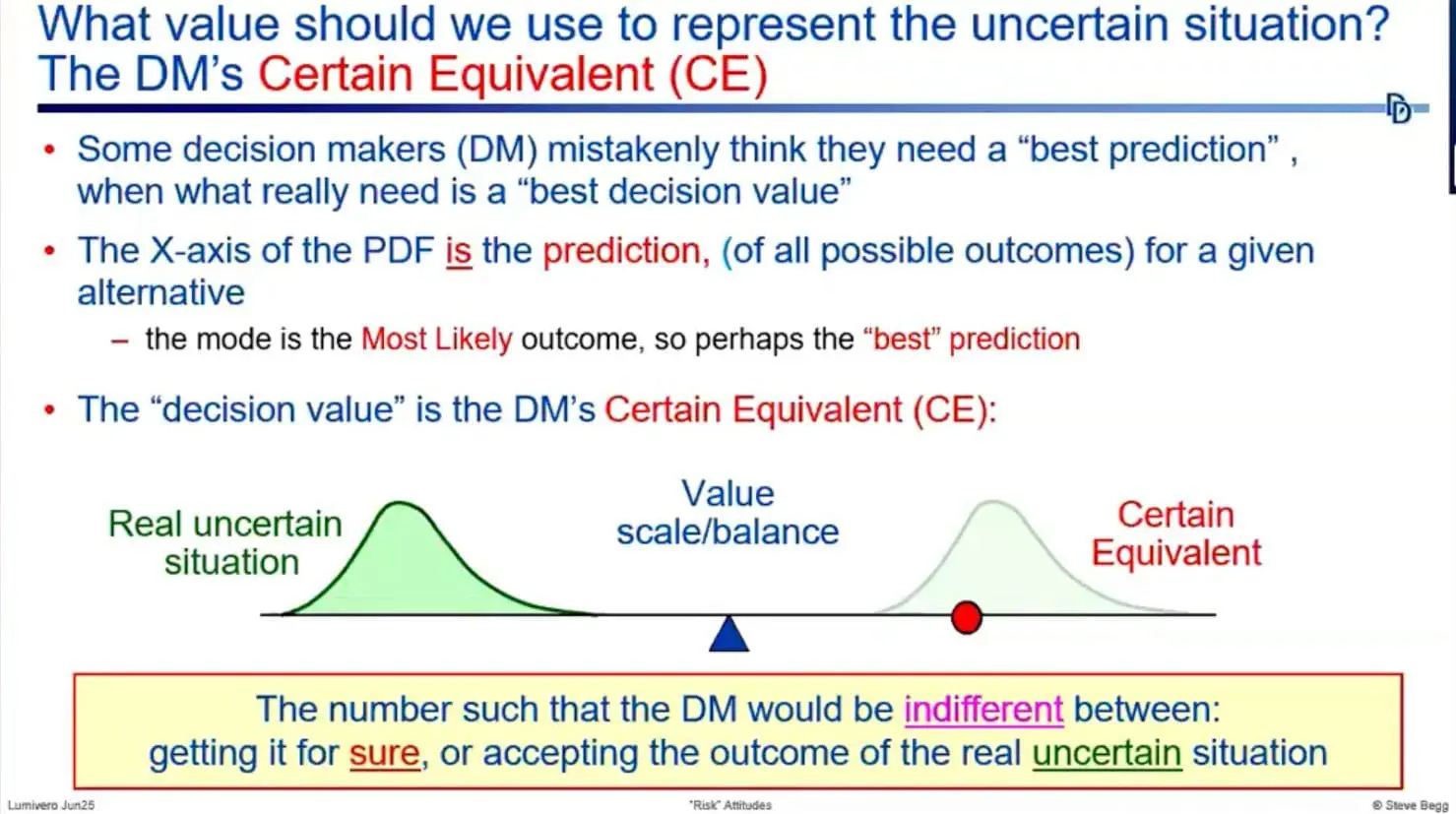

So how can you compare options that are uncertain? Enter the certain equivalent (CE)—often referred to as the “certainty equivalent” in financial circles, as in this Nasdaq glossary. It’s a sure number or outcome that the decision-maker would deem equally desirable to the real uncertain situation with its possible outcomes and their associated probabilities

An example of the DM’s Certain Equivalent (CE). Think of the certain equivalent as a value that balances the scale.

The power of the CE lies in its use to help a decision-maker compare uncertain options. Since the decision-maker considers the CE to be equally desirable to the real uncertain situation, they can just compare the CEs of the competing alternatives to choose the best!

Decision-makers should abandon the seductive idea that they can choose between uncertain options by using a “best prediction”, in the sese of the most-likely (highest probability) outcome. They should also be mindful not to think that, for their chosen option, the CE will actually occur. Any of its possible outcomes could occur, with their given probabilities, including the CE if it is one of the possibilities.

Avoiding confusion: “Best” prediction vs. Certain Equivalent. The certain equivalent will not always match with the most likely (highest probability) outcome.

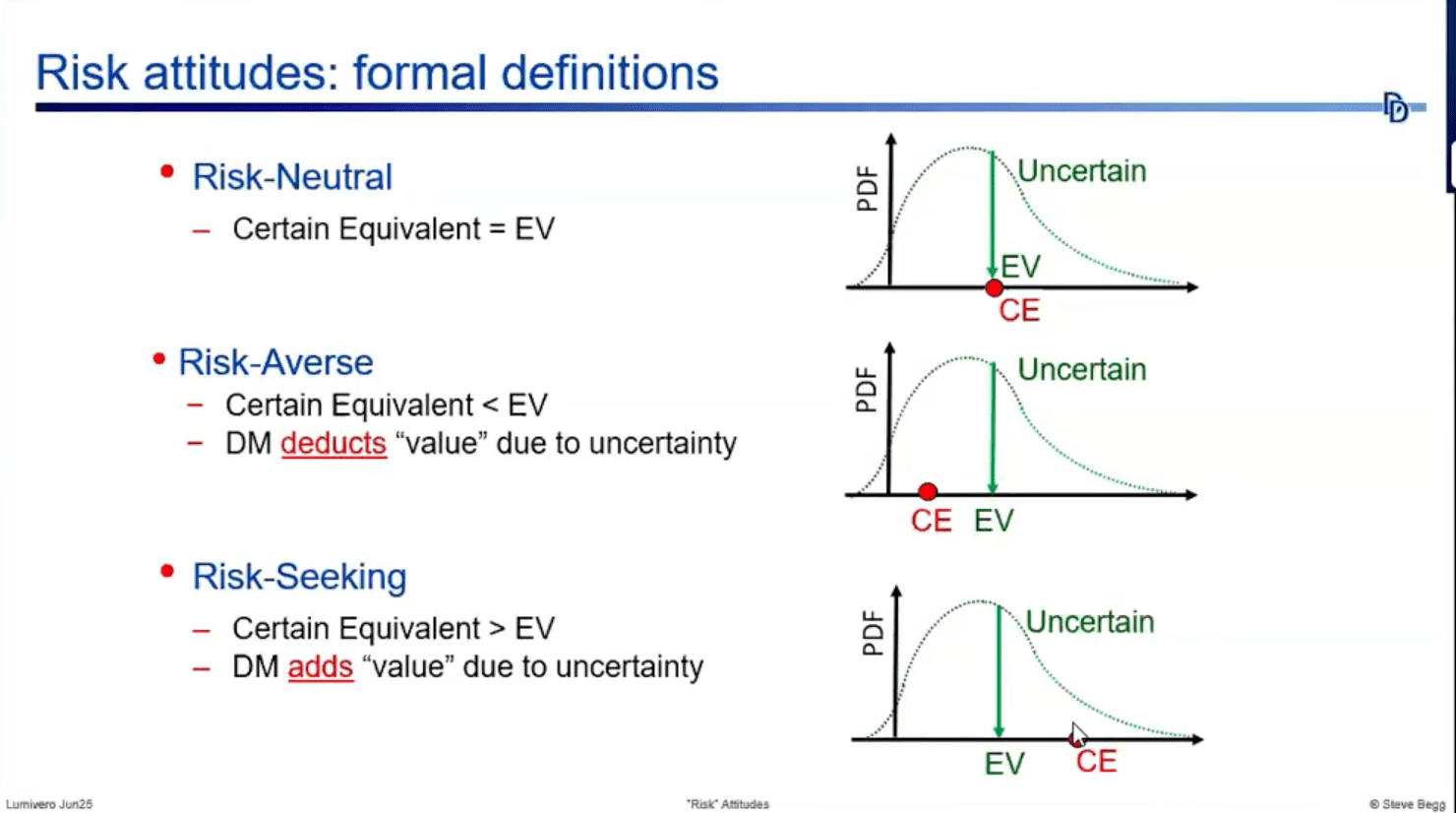

When decision makers understand the certain equivalent, they can begin to re-evaluate and re-calibrate their attitude toward uncertainty. Informally speaking, their risk attitude for any given option is how they weigh its less desirable outcomes (with their associated probabilities) against its more desirable outcomes (and their associated probabilities). So “risk” attitudes, are really attitudes to uncertainty! Formally, risk attitudes fall into three categories: risk-averse, risk-neutral, and risk-seeking—each reflecting a different tolerance for the uncertainty in the outcomes. They are strictly defined by looking at the relationship between the certain equivalent and the expected value (EV) of the probability distribution of the outcomes (the EV is simply the probability-weighted average):

Risk attitudes are determined by the difference of the certain equivalent and the expected value of a decision option.

Our personal attitudes to risk depend on the outcomes relative to our state-of-wealth, and their probabilities. You might be happy to engage in a one-off coin toss where there is a 50% chance of losing $1 and 50% chance of gaining $3 (EV is $1.5). But if the loss was $1,000,000 and the gain $3,000,000 (EV is $1,500,000) you would be risk averse, turning it down because you prefer a sure $0 outcome. Counter-intuitively, a decision-maker can be risk-averse, even if no loss is possible! Would you prefer gaining $1,000,000 for sure, or a 50/50 chance of $0 or $53,000,000 million? If you chose the $1,000,000 you are risk-averse because it is less than the EV ($1.5 million) of the uncertain option, even though neither involves a loss.

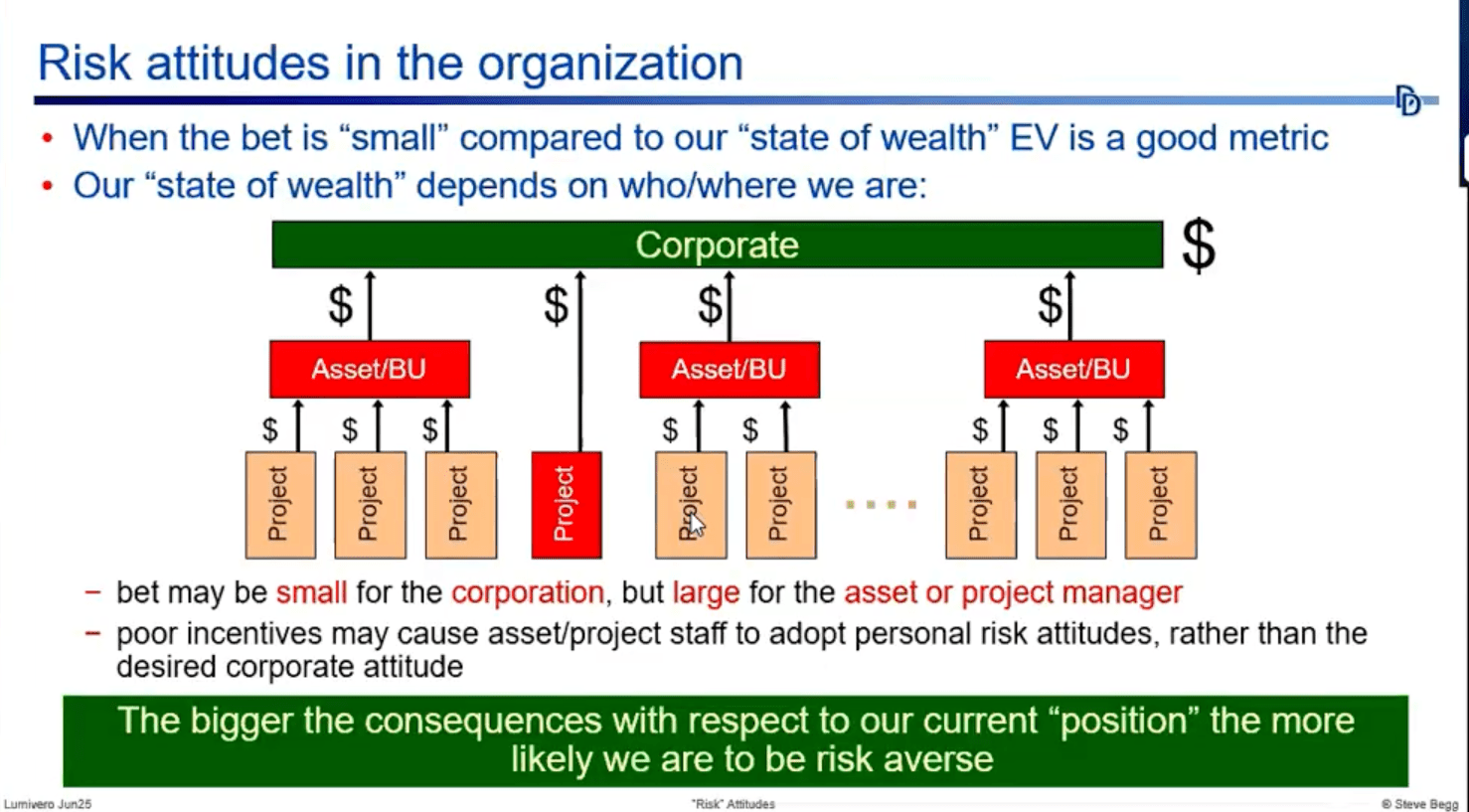

However, issues can arise within organizations when individual decision makers—team leaders or project managers—are incentivized to act as if risks were personal to them, rather than thinking about the organizational wealth structure. Say a decision-maker will not get their bonus if a project does not start on time. This decision-maker might be motivated to choose to do a low EV project, which is very likely to be completed by the deadline. But the corporation, which is doing many projects and so can afford to take more risk, would actually prefer to do a higher EV one, even if it carries a greater chance of being late.

Leaders within organizations need to incentivize decision makers to take a corporate attitude to risk, rather than a personal one.

Risk aversion can actually lead to value destruction, rather than value creation or even value preservation. For example, it may encourage “value engineers” to remove costly flexibility from a project, because that gives an immediate, sure savings. But that saving might be substantially less than the future expected value of the flexibility. Beware of incentives that cause decision-makers to take on personal, rather than corporate, risk attitudes!

Uncertainty should not be relegated to a post-decision risk management activity, or worse, mere compliance. Rather, pre-decision uncertainty assessment should inform the development of value-creating decision options, designed to mitigate risks and to exploit the upside opportunities it presents. The CE can then be used to rank the options and thus help the organization to move away from conservative risk attitudes and realize greater value.

If you’re interested in learning more about risk attitudes and the certain equivalent, watch Steve Begg’s presentation on-demand. You can also begin exploring the possibilities of Monte Carlo simulation-powered risk analysis software and centralized risk management tools: request a demo of @RISK or Predict! today.